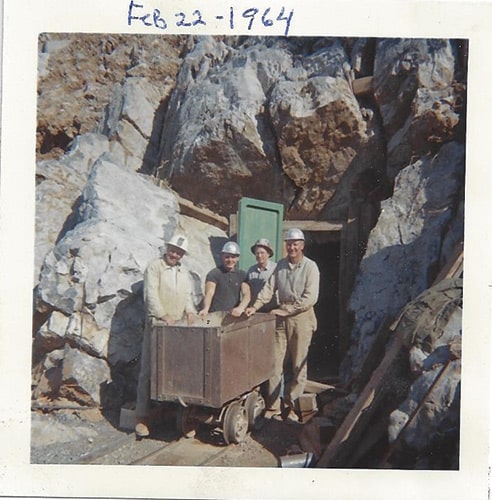

In A Cavern

Lake Shasta Caverns and the International Year of Caves and Karst…

Caves have been friends to people for more than a million years, so it’s only appropriate the geological formations enjoy a year they can call their own. In an effort to raise the level of understanding and respect for caves and karst (topography formed by soluble rocks that includes caves and sinkholes), the International Union of Speleology has deemed 2021 the International Year of Caves and Karst.

“We’re really excited about it,” says Matt Doyle, the general manager at Lake Shasta Caverns National Natural Landmark. The yearlong celebration, which is also being promoted by the National Park Service, falls in line with Doyle’s push to “get people outdoors and get them exploring.”

Although COVID-19 restrictions closed the caverns in the spring of 2020, would-be spelunkers resumed cave tours in mid-June. Doyle says business was brisk throughout last summer, thanks to work-at-home parents taking their distance-learning children on trips.

Interest in the caverns has been steady this year as well. “People want to get out,” Doyle says, noting it doesn’t hurt that the caverns maintain a year-round temperature of 58 degrees (with humidity levels around 90 percent, the air feels like a comfortable 70 degrees). “There’s nothing like seeing people come up for a tour, open that door and get a blast of cool air,” Doyle says.

Lake Shasta Caverns and its smaller counterparts like Samwel Cave and Subway Cave offer more than just a chance to beat the heat, Doyle says. Throughout time, caves provided shelter for all manner of animals and later humans. The caverns are also an amazing repository of minerals, flora and fauna – including the threatened Shasta salamander (hydromantes shastae) – and historical data. Considering the caverns are 250 million years in the making, there has been plenty of time for natural notetaking.

Researchers at Vanderbilt University have been performing climatology studies at the caverns since 2015, taking water samples and learning about the North State climate. Speleothems (stalactites, stalagmites and other formations) “have recorded history from 45,000 years ago. Otherwise, all we have is written records that maybe go back 2,000 years,” Doyle says.

Other scientists have used caves in their research. Doyle says Galileo Galilei, the famous astronomer and physicist, ground the lenses for his telescopes from calcite he collected in caves.

The caverns’ myriad features were noted by the National Park Service well before the International Year of Caves and Karst. In 2012, the park service formally designated the caverns as a National Natural Landmark. The citation referred to the caverns “an extraordinary example of an extremely well-decorated solution cave that possesses an especially diverse assemblage of cave formations at sizes ranging from millimeters to several tens of meters.”

At that time, the caverns joined some 591 other lakes, ponds, caves, swamps, craters, islands, glaciers and volcanoes in the country that enjoy the National Natural Landmark status.

There’s also bioluminescence, the otherworldly light emitted by fungus gnats and their larvae, commonly known as glowworms. “There are so many different properties about caves,” Doyle says. “It’s not just a tourist attraction. There’s so much more behind it. Or should I say underneath it?” •