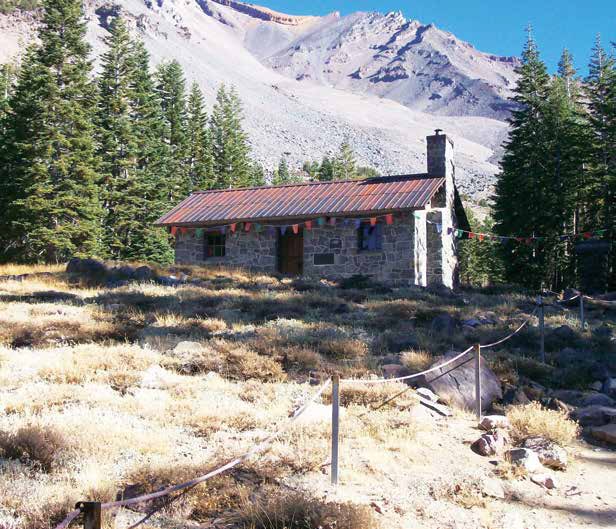

Summit Stop

Sierra Club Hut At Horse Camp…

Built with volcanic rock and alpine timber, perched on the main route to Mt. Shasta’s summit, the Sierra Club’s venerable old Shasta Alpine Hut serves as a rest stop for day hikers, mountain climbers and spiritual seekers. It provides a cool respite from summer heat and a welcome refuge in the winter.

It was built in 1923 at Horse Camp, a level stretch of the mountain where 19th century climbers, including John Muir, left their horses and continued on foot toward the summit. Beginning in 1924, a succession of hut “caretakers” hired by the Sierra Club has been meeting and greeting trekkers from all over the world.

After the cabin was christened with a bottle of Shasta Ginger Ale, the first caretaker, Joseph Macatee “Mac” Olberman, took up residence there at the ripe age of 62, toughing it out for 10 years on the mountain. He was an energetic old fellow. Using a 30-pound crowbar to excavate large rocks, he managed to build a half-mile-long stone walkway toward the summit. It’s known today as Olberman’s Causeway.

To this day, there is still a mystery about him. Despite his rough, mountain man persona, he was well educated and spoke several languages. There were hints, too, of a spiritual side.

In 1968, a young man hitchhiking up Everitt Memorial Highway on his way to the cabin was picked up by an older man driving a red Jeep. The two hit it off right away, and before the ride was over the driver had hired the young man to be the cabin’s next caretaker.

Though neither knew it at the time, a torch was being passed from one generation to another. The older man, Ed Stuhl, had helped build the cabin in the early 1920s. He had gained fame as an artist and botanist with his book, “Wildflowers of Mount Shasta,” featuring his paintings. The younger man, Michael Zanger, after four years as the cabin’s caretaker, went on to write his own books about the history, wildflowers and climbing routes of the mountain and start a successful guide service.

Sharon Overbey has been one of the cabin’s caretakers for nine years now, almost as long as “Mac” Olberman. Over that period she’s seen some changes: Not as much snow, for one thing, in the early part of the season. And due to increased wildfire threats, there are no more evening gatherings with hikers around an open fire pit. (Some half-dozen campsites are scattered around the cabin.)

The Sierra Club keeps caretakers at the hut from the first part of May to the end of September. Overbey works the first part of the season. While she’s at her post, she greets people from all over the country and the world, many of them experiencing the mountain for the first time. At least 10,000 visitors show up at the hut each year, a far cry from the 368 “Mac” Olberman greeted his first year there. Today’s hut visitors include not only hikers and spiritual seekers but botanists following in the footsteps of Ed Stuhl, lured by the unique species of wildflowers found only on Mt. Shasta.

For all of them, she notes, it’s “a time to connect with the beauty of nature.”

When her workday is done, Overbey sleeps in a tent near the hut, peeking out from time to time to marvel at the glittering sky above. “Poetry gets written about experiences like this,” she says.

For those who do head up from the hut toward the summit, climbing conditions can change from one day to the next, or even from one hour to the next.

Case in point: One hut caretaker from the early 1990s, Chet Kyle, was climbing near the summit when a blinding snowstorm enveloped the upper slopes. On his way down toward the hut he encountered two climbers, a man and a woman, floundering around in the blizzard, unsure how to get back to the hut.

Kyle assured them he could get them there safely. But in the blinding storm he took a wrong turn on the way down, and the three of them floundered through the snow and forests on the mountain’s east side until they finally reached the town of McCloud two days later, exhausted and hungry, but relieved to have survived the ordeal.

Mount Shasta, it seems, has lessons for even the most experienced climbers.

“It’s a moody mountain,” says Overbey. “Sometimes it’s beckoning to you with arms wide open. At other times it’s saying ‘You better watch your step.’“