Both Service & Society

The First Woman in the US Forest Service, Hallie Daggett…

In Etna’s city park sits a little wooden cabin, its simple exterior belying the complicated and trailblazing woman who once inhabited it. “What I think is remarkable is how much the citizenry of Etna recognized how extraordinary Hallie Daggett was, and how important it was to preserve the legacy of her life and her home from her later years,” says Patty Grantham, coordinator of the Siskiyou Prescribed Burn Association, who spent more than 40 years with the Forest Service. For Grantham, Hallie has long been an idol. “While I have been a ‘first’ a number of times in my career in both firefighting and in leadership positions, what I think is important to emphasize is that Hallie was the first woman in the U.S. Forest Service, period. And in the 111 years since, everyone else has just followed in her wake.”

Hallie Morse Daggett was born December 19, 1878, in what is now the ghost town of Liberty, California. Her father, John Daggett, was a wealthy businessman who owned and operated several large gold mines near Sawyers Bar, California, while simultaneously hobnobbing with the San Francisco elite. As one of this three surviving children, Hallie grew up straddling both worlds, along with her sister Leslie. “John Daggett raised his kids in the Salmon River country, where they were exposed to a western lifestyle of self-reliance and community. They also had the blessing of being exposed to San Francisco society and strong education opportunities. Hallie and Leslie ended up both staying in this area throughout adulthood, which I think that says a lot about their connection to the natural world and this particular landscape.”

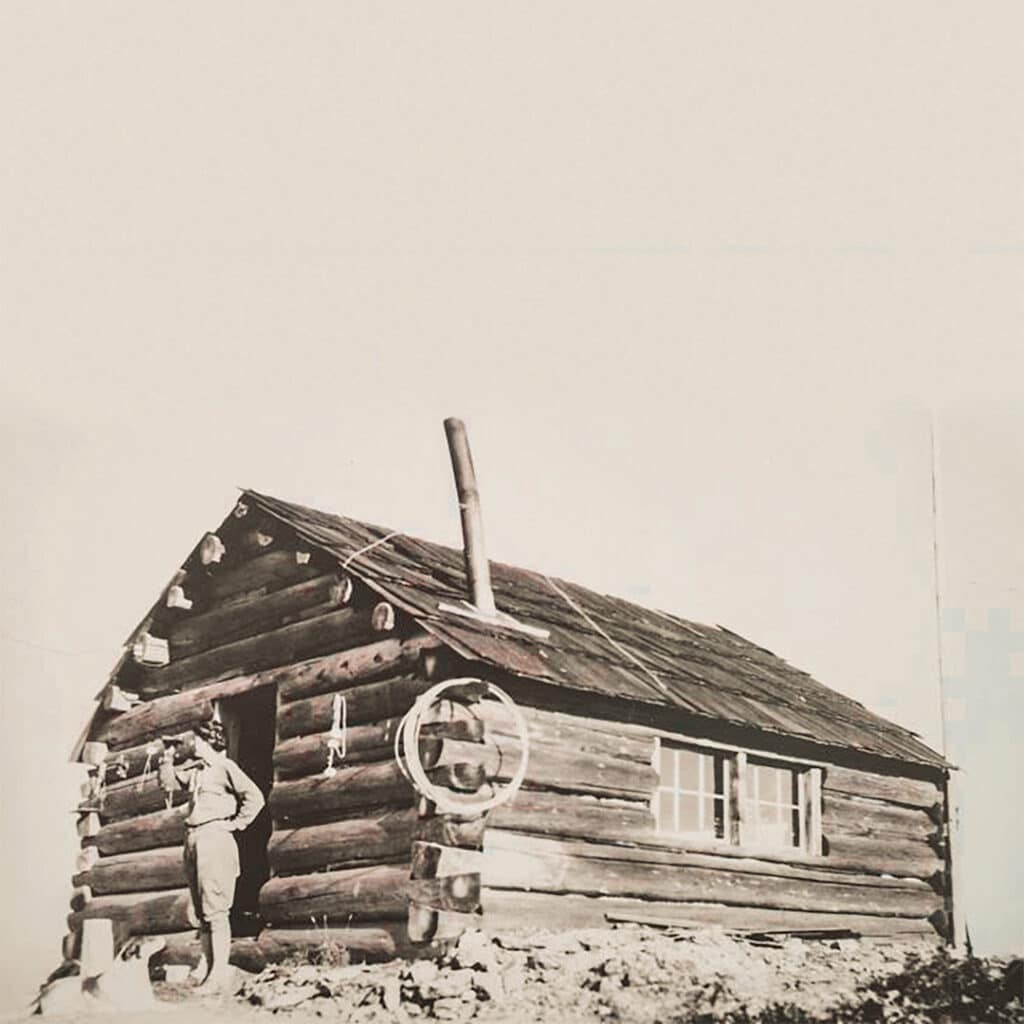

But in May 1913, Hallie’s life took an unexpected and historic turn when she was hired as the fire lookout for Eddy Gulch. Considered “something of an experiment,” it was the first time any woman had ever worked as a field officer for the agency. But with a shortage of suitable men in the running, and Hallie’s persistence, an opportunity finally presented itself. “She was 35 years old when she accepted the job. But she had lived her life in these mountains, and she had a reputation as a very capable outdoorswoman. And I mean, that’s really the only way the Agency and the forest supervisor at that time would’ve gotten away with putting a woman into this position,” says Grantham. Grantham also underscores the difficulty of what the job entailed. “You say ‘fire lookout’ and some people have this immediate vision of a person in a tower with a spotting scope or binoculars locating the smoke out and conveying that information to somebody else to take care of the fire. Well, back in her day, Hallie was often the person who took care of the fire, too. When telephone lines weren’t working, which was often the case, she’d put on a pack, walk to the fire, and put it out with an axe and shovel. I always like to talk about her in that context because it wasn’t just a lookout job.”

This “experiment” ultimately turned into 14 years of service for Hallie, and paved the way for other women to follow in short order. “Maybe the blessing is that she wasn’t living in a social media age, so things didn’t quite blow up as quickly. It probably took a year before the chief of the Forest Service even realized there was a woman working for his agency. By then, it was too late. And soon, a number of other women took fire lookout positions. That was mostly a reflection of World War I, and the shortage of men to take these jobs, but Hallie had proven women were capable and could handle themselves in the outdoors. You can imagine if something terrible had happened with respect to Hallie’s time in service. It would’ve been a setback for all of us,” says Grantham.

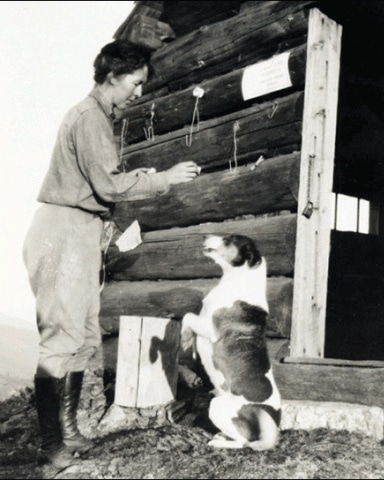

Grantham also likes to acknowledge the unsung role that Hallie’s sister Leslie played in her success. “Every week during Hallie’s 14 seasons as a lookout, Leslie would saddle up her horse and pack mule and head to Eddie Gulch to bring Hallie her supplies and mail. I think it was about a six- or eight-hour round trip ride up, and anybody who’s been in the saddle knows that that’s not much fun. But that part of the story has always touched me because I feel deeply that our families are a big component of our success in public service.”

When Hallie finally turned in her resignation in 1927, her supervisor tried to refuse. “By this point, we were well out of the war years, so he would have had several capable male candidates but he didn’t want to let her go. Ultimately, she did retire to Etna, living the rest of her life in a little cabin some friends built for her. Eventually that cabin was moved to the city park for preservation. But she’s been a tremendous influence on my life,” Grantham says. “And this may sound a little cheesy, but one of the things Hallie did every day at the Eddy Gulch station was raise the American flag, which she continued to do at her house every day after she retired. And I still put the American flag up every day at my house, too.” •

Hallie Daggett’s cabin can be viewed today at Etna City Park.