Cooling Cascades

On The Trail To Koyom Bukum Sewinom Bo…

Smack dab in between North Lake Tahoe and Redding on scenic Highway 89 is a nice little pullout just outside of Quincy and Taylorsville along the Feather River with a sign that says Indian Falls.

The pullout turns into a single-lane dirt road/parking area shaded by tall oak trees and Douglas Firs. If you get out and stretch your legs, you may notice a sign at a trailhead close to where you pull in that explains that the 600-foot trail down to the torrents was originally called the “Koyom Bukum Sewinom Bo,” meaning “Valley End Falls Trail” in the native Maidu Indian language.

The wide, flowing cascades at the bottom of the dirt, pine needle and leaf-packed path were important to the Maidu people, who have lived in the central Sierra Nevada along the Feather and American River watersheds for many generations. They spoke four different languages within the Maidu culture, yet all resided close to each other in Plumas and Lassen counties.

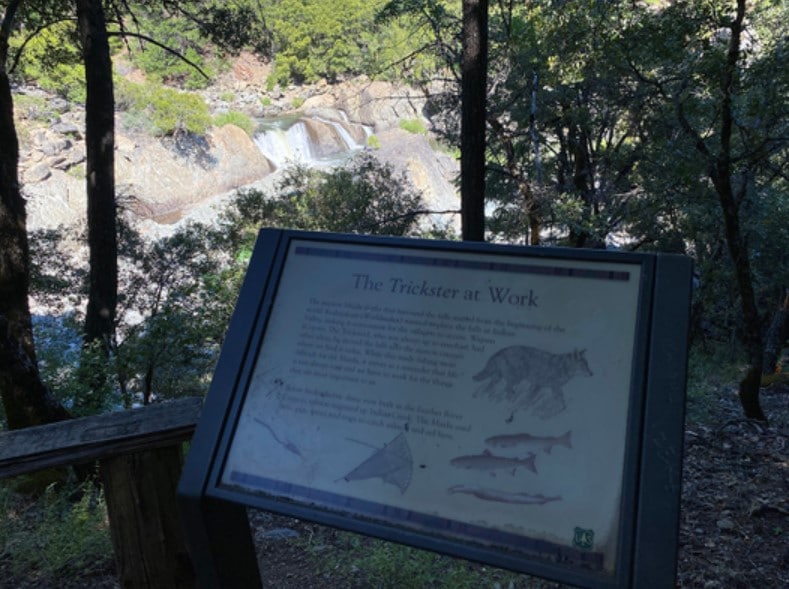

The Maidu believed that a higher being (the Worldmaker) meant to place these shelves of flowing waters in Indian Valley in a location that would be easily accessible to the villagers. However, a coyote that the Maidu called the “Trickster” moved it into the narrow canyon of the Feather River where it’s found today. Its tough location made fishing for salmon a bit more difficult, but it didn’t seem to bother them too much; it just reminded the Maidu people that life isn’t always easy and one has to work for things that are important to them.

Nowadays the hydroelectric dams keep salmon from migrating up Indian Creek, but back then the Maidu used nets, spears and traps to catch eel and fish.

The short hike down to the falls rests under ancient black oak trees that drop large acorns that Maidu hunters and gatherers foraged and used as a staple in their meals and kept in their intricately woven sturdy baskets made of willow reeds and tule roots. After scooping up the acorns, they would then cut them with water to leach out the tannic acids and make them edible.

The path is peaceful and quiet, except for the distant hum of the cascading waters that gets a little louder as you get closer to the falls. Open year-round, look closely in early summer and you’ll find gentle purple wildflowers interspersed in all shades of green, which unfortunately includes poison oak (so don’t venture too far off the trail).

It’s an easy, quick trek until you get to the first viewpoint of Indian Falls, where a moss-covered wooden picnic table allows one to sit and take in the beauty of the canyon. However, especially on hot summer days, many people continue down to the actual river that spans from Lake Oroville to Yolo County to wade into the clean clear pools that form below the falls. It’s common to see Feather River College students on summer break sunbathing on the flat slabs of rock or relaxing in the water atop a unicorn floatie.

To get down to the bottom of the canyon and go swimming, one will have to unleash their inner mountain goat and creatively use semi-loose rocks as footholds on this undeveloped part of the trail. It’s entirely at your own risk to get down there, but it’s fun to jump from rock to rock and find smoothed out tidepool-looking crevices that could’ve been manmade mortars ground into the solid rock.

Indian Falls is one of Northern California’s hidden gems, kept intact and resplendent while subtly sharing Native American history. However, on a long road trip on Highway 89 it’s easy to miss, so remember to stop and stretch your legs occasionally and you might stumble upon something like Indian Falls.